A year on the farm: Disaster, chaos, general annoyance, and a true love of farming

19th November 2021

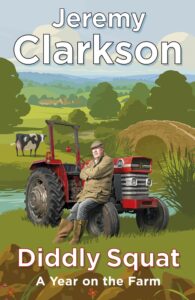

After Clarkson’s Farm aired on Prime Video, viewers tuned in to witness farm manager Kaleb Cooper regularly lose his temper with Jeremy Clarkson’s attempts at farming. Now, Clarkson’s much-awaited book, Diddly Squat: A Year on the Farm has been released. Farmers Guide got hold of a copy and it is everything you would expect and more…

The story of how Jeremy Clarkson came to swap racing around in cars for farming is now well known. Having bought his 1,000-acre farm in Oxfordshire in 2008, he rather confidently decided to run it himself when the farm manager retired in 2019 – with an air of ‘what could go wrong?’.

As anyone who watched Clarkson’s Farm now knows, many things went wrong.

When Covid-19 hit, Clarkson found himself with no cars to review for his Sunday Times column and decided to write about farming instead. His latest book is a collection of these stories and they are every bit as hilarious, irritable, educational and occasionally heart-warming as any Clarkson’s Farm fan might expect.

Charting an entire year on the farm, the book is filled with Clarkson-esque quips and laugh-out-loud entertainment. It manages to provide light and joyful escapism, whilst getting across the serious challenges of farming – from the industry’s high suicide rate and problematic health and safety record; to the impacts of Brexit, Covid and extreme weather; to the struggle to be profitable and keep up with unprecedented levels of change.

Red tape and obnoxious sheep

Clarkson is clearly not a fan of the government, describing it as ‘endlessly annoying’, taking a swipe at ‘George Useless at the environment department’, and noting that ‘in farming you have to ask the government’s permission to get up in the morning’. He also takes issue with the government’s ‘public money for public goods’ approach, explaining: ‘In other words I won’t get cash to help me grow food for humans; only for newts.’

Perhaps the only thing he appears to dislike more than the government is sheep, which he describes as an ‘expensive nuisance’. Clarkson’s Farm viewers will be no strangers to his endless attempts to recapture his escaping flock, even resorting – unsuccessfully – to using a barking drone to keep them in line.

Pages of the book, however, are dedicated to chronicling his sheep’s failings in depth – aside from being akin to ‘woolly teenagers’ whose only aim is to die horribly, Clarkson says they ‘take absurd risks and feign a lack of interest in everything, while deliberately being obstructive, stubborn, rude and prone to acts of eye-rolling vandalism’.

To add insult to injury, as all sheep farmers will be aware, Clarkson lost around £1.20 per sheep at shearing due to the incredibly low wool cost – but on a positive note he saved thousands using the wool as a sustainable wall cavity filler in his house, which seems to have redeemed the sheep slightly in his eyes.

Unsurprisingly, the book also contains a rant about Clarkson’s R8 270 DCR Lamborghini tractor, which the farming community would unanimously agree is ‘too big’. He reluctantly admits that he can’t attach anything to it, had to rebuild his gate and barn to accommodate it, and is perplexed by its 48 gears and 188 buttons. So far, he has crashed it into six gates, a hedge, a telegraph pole, another tractor and a shipping container.

On a serious note

While Clarkson chronicles the everyday calamities on the farm, the frustrations and roadblocks faced by farmers is clear – from the durum seeds that got stuck in France due to Brexit and the loss of 10 acres of OSR to flea beetle; to having to deal with the ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ (aka the parish council) when starting his farm shop, and finally the gaggle of kids that show up to use his farm as a toilet while their supervisor blocks the track with his Peugeot.

In amongst the hilarity there is a serious side to the book, where Clarkson shares key concerns in the industry – the wide variety of health and safety risks and the disproportionate number of deaths and injuries as a result; as well as the industry’s mental health challenges.

Clarkson tackles the public misconception that farmers are rich – he is candid about the huge costs of machinery and equipment and the falling returns. When he begins selling his lambs, he is getting £100 per lamb – two weeks later this has dropped to just £30. He also writes of the ‘real heartbreak’ when he finds his barley yield is down 20% – and thanks to Brexit, prices take a hit too. There is a serious edge to his joke that he would have to charge £140 per broad bean and £400 per cabbage to be profitable.

It may surprise non-farming readers to see Clarkson’s acceptance that he will ‘almost certainly’ make a loss on every ounce of wheat, barley and OSR he has grown, but he cheerfully predicts that ‘with a fair wind’ he’ll lose ‘only’ about £500 a month on his farm shop.

There is a sense of frustration, and perhaps sadness, that he struggles to understand aspects of agriculture that seem to come naturally to what he calls ‘proper farmers’. Yet there’s also a sense that while he’s still new to farming – and famously and hilariously inept at certain farm tasks – he is not alone in his struggle to understand the overwhelming change British farmers are facing, nor his fear that he will ‘drown in tech I don’t understand and can’t afford’.

He writes: ‘I think there are a lot of farmers like me who are bewildered and even a bit frightened by what they must do to survive. And I think you, round your breakfast tables, should be worried too.’

The joy of farming

Between rants, disasters and concerns for the future, it is clear that Clarkson’s love of farming is genuine. When he first announced his decision to give ‘farmering’ a go, you could be forgiven for thinking it would be a short-term experiment. But, perhaps to his own surprise, he describes it as ‘utterly joyful’.

Diddly Squat: A Year on the Farm is a perfect blend of hilarity and frankness that farmers will empathise with and the public will learn from. It is essentially a sarcastic, hilarious love letter to farming. Agriculture may not be the ‘festival of crusty bread, lemonade and fresh air’ with a ‘big fat cheque from the EU’ that Clarkson was expecting – but he paints an idyllic picture of farming, describing it as a ‘wellness spa’ where he drinks water from his own spring and eats bread made from his own wheat.

He freely admits he is not ‘remotely inclined to go out in the middle of January to mend a gate’, and ‘either I don’t know what I’m doing or I can’t be bothered to do it’. But when he considered moving back to London after a year on the farm, he writes:

‘It was a lovely September day and the leaves in the trees were beginning to go orange and brown and red and I looked back on what I’d learned over the previous 12 months and I knew I wanted to stick around. Even if I was only being paid forty pence a day.’

Diddly Squat: A Year on the Farm is published by Penguin (£16.99).