Farm turns around high SCC by tackling dry period infections

23rd December 2021

Last year, Adrian Bland of Ninezergh Farm began taking steps to tackle increasingly high somatic cell counts in his 120-cow milking herd. Just over a year on, he took part in a recent AHDB webinar to explain the farm’s progress.

Ninezergh Farm, an AHDB strategic dairy farm based in Levens, Cumbria, is split across four separate blocks and milks 120 autumn calving crossbred cows. There are also 550 sheep and 120 beef animals from the dairy herd which they raise to 24 months old.

Due to pressure on milk prices, the farm had stopped milk recording for a period of time to cut costs. While things ticked along for some time, they started to see high somatic cell counts after calving in 2019, which worsened in 2020. This prompted Adrian to seek help from vet Andrew Crutchley and Dr James Breen from Map of Ag and the University of Nottingham.

When they began collecting data again in October 2020 and using software to pick out trends, it became apparent that the dry period was key to new infections on the farm. During a recent AHDB webinar, Dr Breen said: “If we’ve got cows who are above 200,000 cells/mL in their first milk recording post-calving, the research is clear – it’s likely an infection they already had when they calved – this immediately points to the dry period.”

Dr Breen stressed that treating high cell count cows in lactation is not the answer – instead, it’s important to focus on new infections and use regular individual data to track high cell count infections and determine their origin.

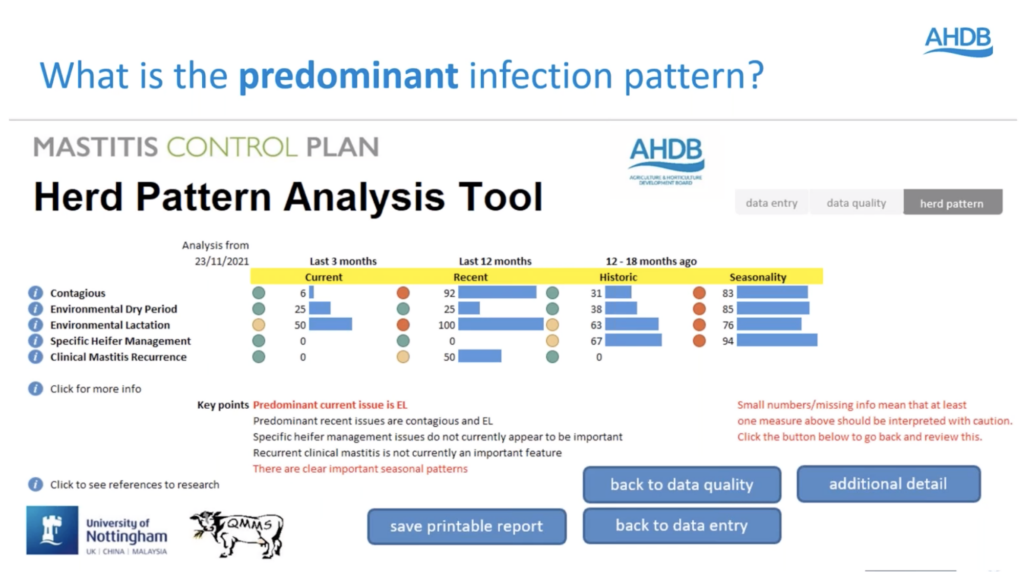

The key aims for Adrian’s farm were to tidy up high SCC cows in the dry period and avoid reinfection. They began using AHDB Dairy’s QuarterPro scheme which offers a number of resource materials, as well as a tool by QMMS and Sum-IT that allows farmers to load milk recording data and identify infection patterns in the herd.

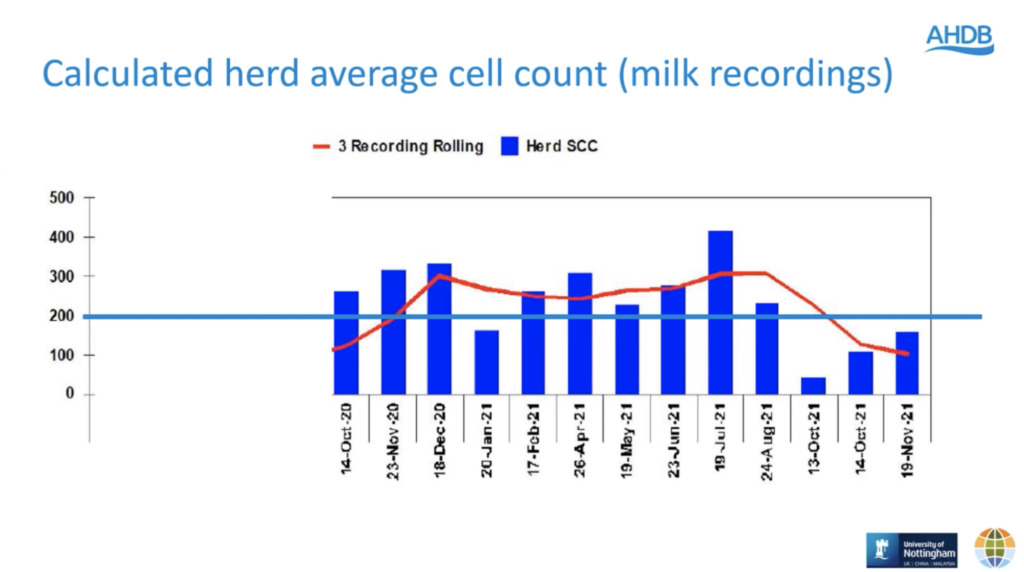

Data from Adrian’s farm show very high average cell counts in October 2020, which continued into 2021. This season, test days in October and November show much lower cell counts compared to the previous year.

Problems identified

With no individual data, the farm had previously been using a blanket dry cow therapy across the herd and only had high cell counts post-calving in September and October, which then settled down. “We lived with that for 2-3 years but it crept up […] until 2020 when it got over the threshold. We got very close to a serious penalty in September so we decided we had to attack it,” Adrian explained.

The farm had also stopped using teat sealants around eight years ago when the milk price was very tight, dropping down to 20ppl and Adrian said “you just cut every corner you could”. When it appeared that there had been no negative impacts from stopping, however, they decided not to begin using them again.

“We cut corners and things didn’t seem to be broken so we carried on and slowly but surely it crept up on us and, let’s be honest, we ignored it [until] 2020 when the somatic cell count got that high, we had to do something,” Adrian said.

Post drying off, cows were rotationally grazed where possible, came into the paddock three weeks prior to calving and were put on a TMR from a feed trailer, on a bare paddock with a few sheep keeping it bare.

The farm had to some extent become a victim of its own success, Adrian explained. As fertility improved, the calving pattern got tighter and tighter, resulting in a peak of 42 cows in the 3-acre paddock at one time, putting pressure on the paddock.

Hygiene protocols for dry cow therapy also needed improvement, Adrian acknowledged: “We were less careful on procedure, believing we were solving the problem we may be creating by using antibiotics. That’s not good practice by any means.”

Dr Breen noted: “It’s a very common misconception that because we’re putting antibiotics in it doesn’t matter, but you absolutely can still infect cows – especially since dry cow antibiotics tend to be quite narrow in terms of their activity against bacteria – but you don’t tend to see the dramatic symptoms.”

Management changes recommended by the farm’s vet Andrew Crutchley focused on dry cow management, including:

- Internal teat sealant for all cows at drying off. Dr Breen stressed that the research evidence on internal sealants is very strong, while the evidence is lacking on efficacy of external sealants.

- Changes to ensure hygienic infusion technique (cleaning and wiping bags with alcoholic wipes and working from front left to back right).

- Any cow that had mastitis in the last lactation automatically received antibiotics.

- A slatted building next to the calving paddock, which was previously used for rearing and fattening, was repurposed for dry cows. Temporary cubicles were built and rubber mats put down, with eight cows per pen. At the end of the slatted building was one straw pen bedded daily with sawdust.

- At the start of the season cows were given big bales and dry cow rolls instead of the TMR used for the past 20 years which Adrian says worked “exceedingly well”.

- Time saved by not making the TMR allowed time for bedding close to cows daily.

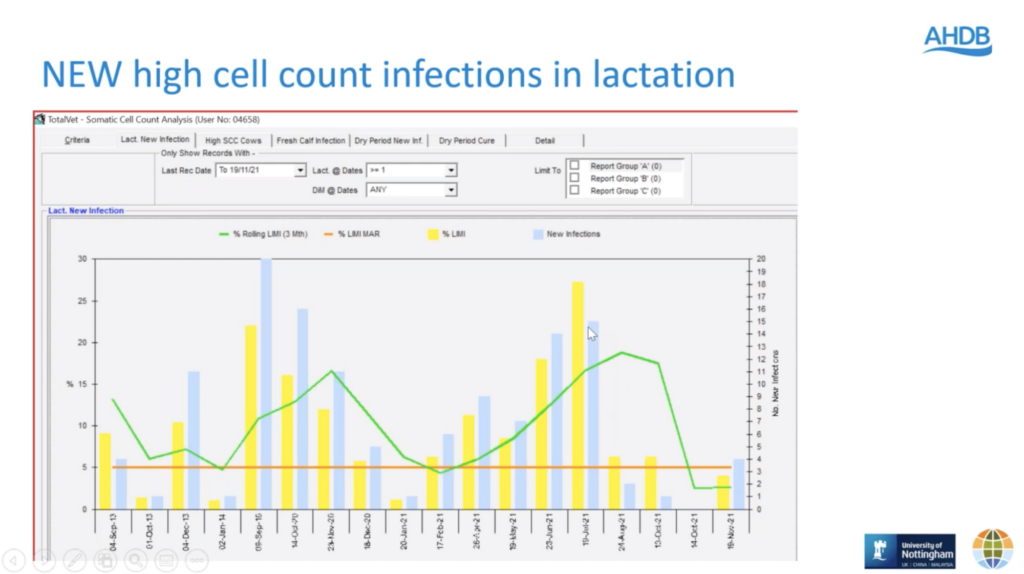

Data showed a surge in new infections in milkers in summer 2021, which occurred as a result of the farm stopping teat spraying pre- and post- milking. Once teat spraying recommenced in August, the new infection rate dropped significantly.

Outcomes

After implementing these changes, the herd average SCC was much lower than the previous year, Dr Breen said. In November 2021 the dry period new infection rate was zero and of the cows that dried off with a low SCC, none calved back in with a high SCC.

Looking at the dry period cure rate using a rolling three recording average, on average 87% of cows that dried off above 200,000 cells/mL calved back in below 200,000. There were also very few mastitis events in the first 30 days after calving.

However, Adrian admits that there was a surge of new infections in milkers in summer due to a change in practices. Cows were turned out in early March and as it was such a dry summer, they stopped teat spraying pre- and post-milking as cows were coming in spotlessly clean. This resulted in new infections creeping in.

As soon as they started calving, they began teat spraying again and reported that the new infection rate dropped like a stone.

“It reminded me that there’s no silver bullet to solve any problem and you can’t afford to switch off at any time and get lazy,” he said.

A tool by QMS and Sum-IT allows data to be analysed at the click of a button to highlight infection patterns. This data from the last three months on Adrian’s farm shows the predominant infection pattern is no longer the dry period, but environmental lactation.

Can this model be applied to other farms?

Commenting on how other farms can apply this scenario to reducing cell counts and clinical mastitis on their own farms, Dr Breen stressed that there is no one size fits all, but there are some key take home messages.

“Mastitis control is not simple. Current infections will cure in the dry period but it’s all about prevention. You must prevent new infections – but that in itself is not simple.

“Where do new infections come from? People tend to still talk about transmission a lot and culling. For some herds, contagious spread is important but for a lot of herds it’s environmental, which is much more complicated – it can be a real challenge to know where the predominant new infection risks are.”

He added: “Because farms and pathogen profiles are different, solutions need to be herd specific. Look at your herd’s data and design a small set of control measures that will have the most impact.

“Don’t focus on cows that are already infected. […] Focus on where new infections come from. You need milk recording and mastitis data to identify a predominantly dry period or lactation infection pattern – as we’ve seen, the control measures for each are very different.”

Key take home messages:

- Individual cow milk recording – CIS, NMR or QMMS – is key

- Record all clinical mastitis events

- Use individual cow monitoring with AHDB Dairy’s QuarterPro scheme

- Ask your vet to focus on new infections

- Do more than 10% of cows calve into the herd with a high cell count over 200,000 cells/mL?

- Is your infection pattern predominantly dry period?