Growers risk serious escalation of black-grass problems

10th August 2020

Many growers across the country are risking a serious escalation of their black-grass problems by failing to pay sufficient attention to key elements of cultural control, according to the latest national grassweed study run independently for Bayer this season.

Many growers across the country are risking a serious escalation of their black-grass problems by failing to pay sufficient attention to key elements of cultural control, according to the latest national grassweed study run independently for Bayer this season.

The Roundup study, involving almost 200 growers across the country and an arable area of 45,000 ha, shows that those with the most serious black-grass problems are continuing to bear down hard on the weed with comprehensive cultural controls.

Unfortunately, however, growers with definite but less widespread problems with the grassweed are placing very much less emphasis on almost all the most important black-grass management techniques. What’s more their use of many of these controls appears to have declined noticeably from the most recent parallel study in 2016.

“The latest results from our series of studies dating back 20 years suggests encouraging progress is being made in getting on top of our biggest national grassweed threat,” comments Bayer weed control specialist, Roger Bradbury.

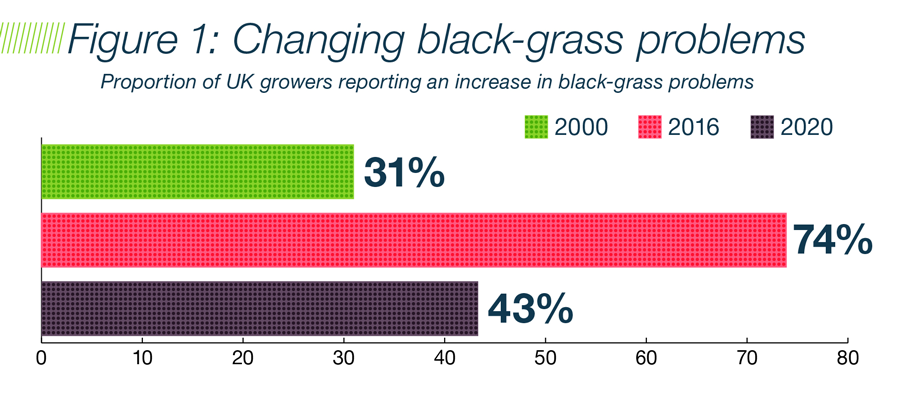

“Unsurprisingly, more growers are reporting increased black-grass problems than they did in our first study in 2000. But noticeably fewer are doing so today than four years ago (Figure 1).

“The fact that this change is consistent across every part of the country suggests it’s not merely due to any difference in the geographical spread of farms involved.

“More of those in the east and East Midlands and the north and Scotland are still seeing an increase than a decrease in their black-grass problems, albeit much less so than in 2016. But, interestingly, more growers in the west Midlands and Wales and central and southern England are now reporting a decrease than an increase.

“Encouraging as this position is, we’re very concerned by the latest intelligence we’re getting on cultural control programmes,” he reports.

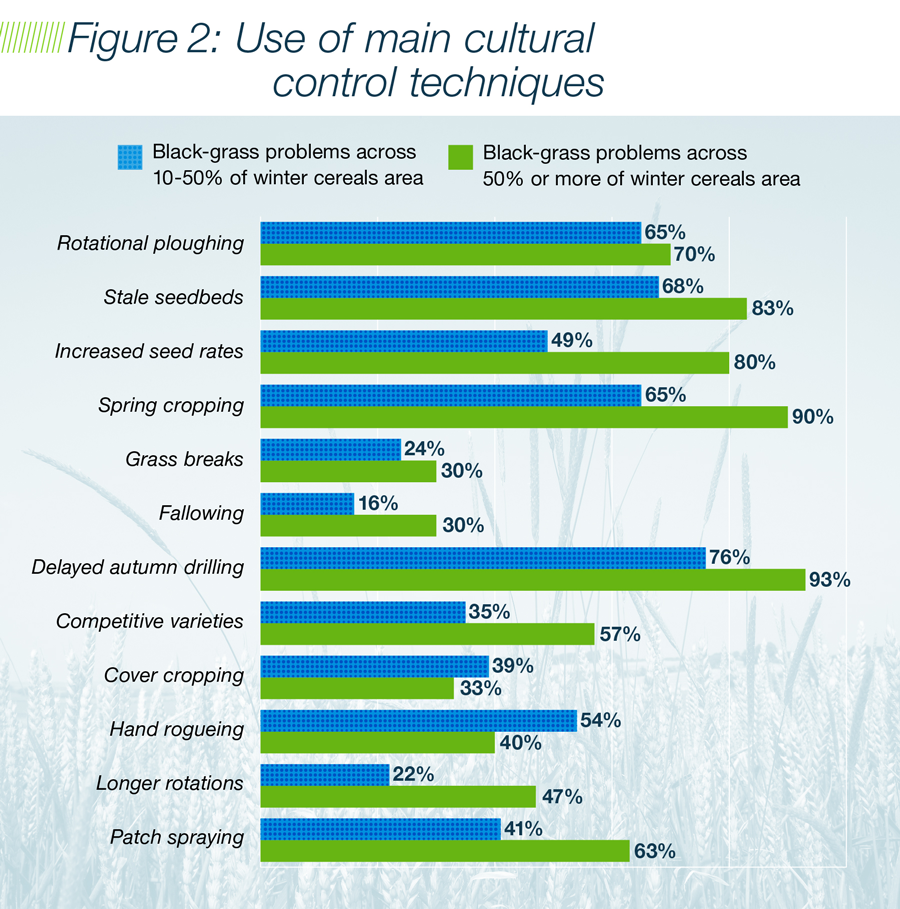

The 2020 study shows growers with the worst black-grass problems practising a commendably high level of cultural control. They are employing an average of eight of the 12 main techniques in their management, with a particularly high use of delayed autumn drilling, spring cropping, stale seedbeds, increased seed rates and rotational ploughing (Figure 2).

In marked contrast, those with known but less widespread black-grass problems are only employing an average of six of these techniques and 10 of them noticeably less frequently.

“We would, of course, expect to see rather less emphasis on cultural controls among those with less serious weed problems,” Mr Bradbury accepts. “But the extent of the reduction is what really worries us.

“To find barely two thirds of growers with black-grass problematic across up to 50% of their winter cereals employing stale seedbeds, rotational ploughing and spring cropping, and only around three quarters delaying their autumn drilling is sobering when we know how crucial these practices are.

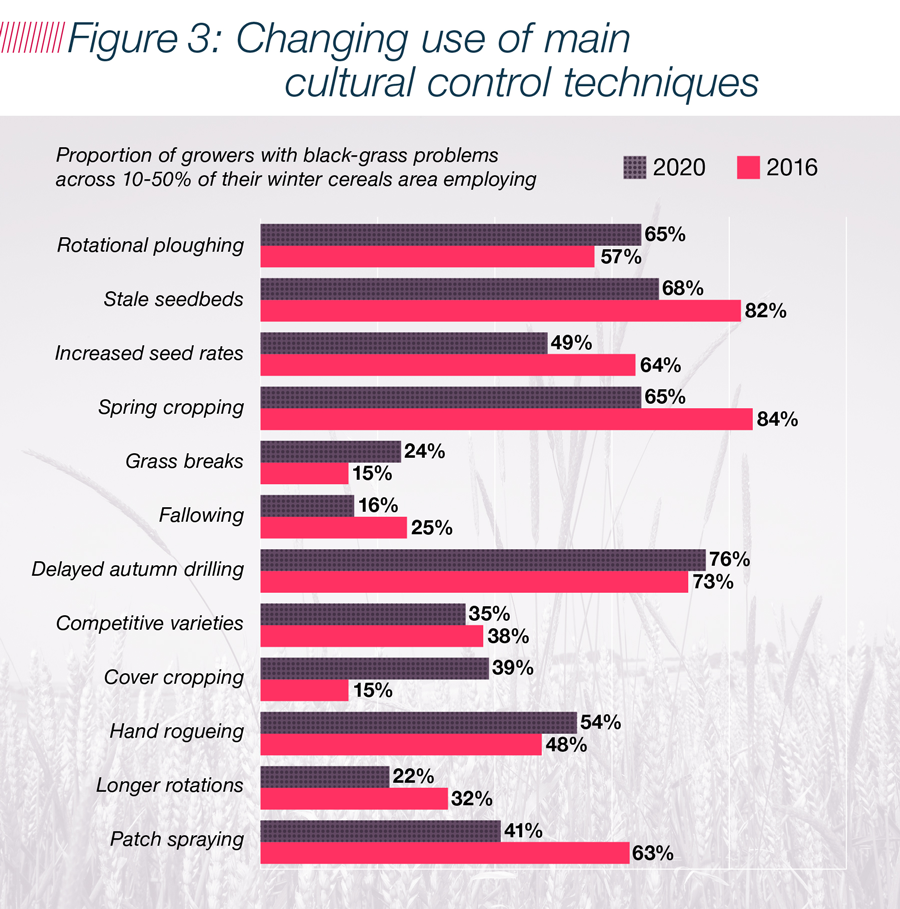

“This is especially worrying when our 2016 study showed over 80% of those with similar levels of black-grass employing both stale seedbeds and spring cropping (Figure 3). Thankfully, we see relatively little change in the use of delayed autumn drilling, rotational ploughing, grass breaks, fallowing and hand rogueing between the years. And the use of cover crops has clearly increased despite their value in weed control remaining in dispute. But marked declines are obvious in the proportion of growers using six of the 12 techniques.

“Knowing how rapidly black-grass infestations can grow and the damage they cause, it is essential that even those with less extensive problems today maintain first-class cultural control,” insists Mr Bradbury. “All the more so, with over half the growers in our study now reporting serious or very serious herbicide resistance problems. That this is not happening rings clear warning bells.”

Nor is this reduction in cultural controls being balanced by any attempt to increase autumn chemical control. Indeed, quite the opposite.

Over 95% of those with the worst black-grass problems are employing glyphosate ahead of planting for the cleanest possible start to their next crop, with more than half of these using the recommended optimum of two applications.

A similarly high proportion are prioritising pre-em herbicides, and 40% of these are also using a peri-em to bear down hard on black-grass at its earliest, most vulnerable stage.

While over 90% of growers with less extensive black-grass problems are also using pre-planting glyphosate, only around 20% of these are treating twice. At the same time, the proportion using a pre-em falls to just 76%, with less than 20% using a peri-em treatment.

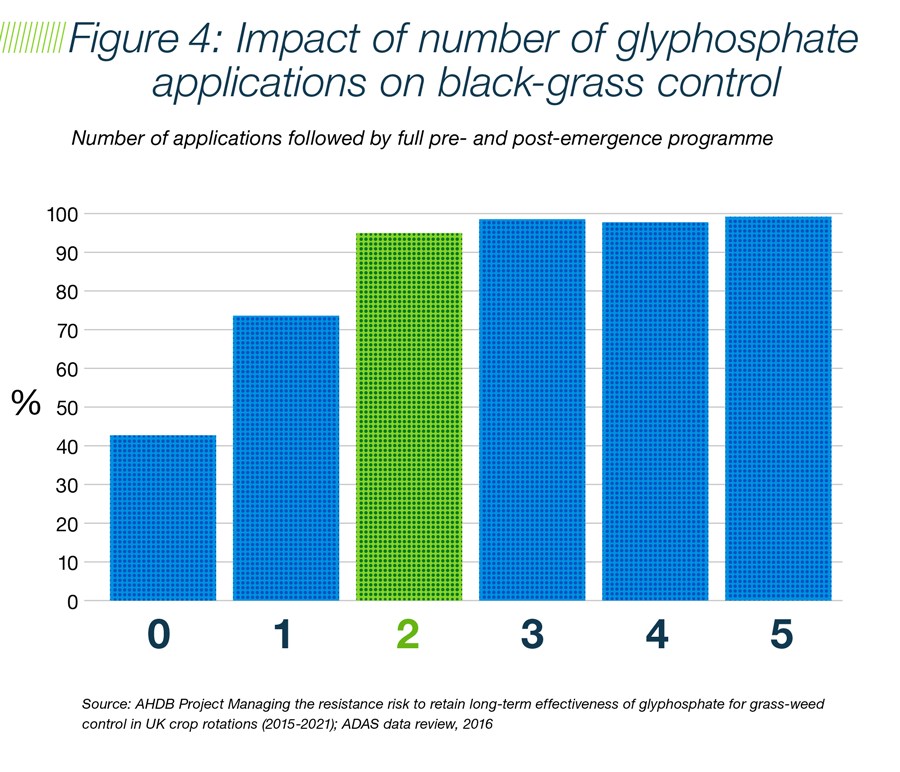

“We wouldn’t expect to see peri-em usage, in particular, at the levels of those with the worst black-grass problems,” Mr Bradbury says. “But a quarter of people with clear black-grass issues on their farms not using a pre-em has to be a big concern. Especially so, as the majority are sacrificing considerable control by only using a single glyphosate application rather than the optimum of two ahead of planting (Figure 4).

With two thirds of those deliberately delaying autumn drilling in the 2020 study only using a single glyphosate application ahead of planting, Mr Bradbury identifies a clear opportunity to improve black-grass control here for many.

However, he acknowledges that there are establishment regimes that do not easily lend themselves to more than one pre-planting application. Equally, very dry weather through September can seriously limit any early black-grass flush – even in a low dormancy season.

“So, where you relying on just one treatment you have to make it count,” he stresses. “This makes it more important than ever to employ a modern Roundup formulation proven for its reliability under challenging conditions, and at the right rate.

“All our trial work and experience shows we get the optimum control of black-grass with two pre-planting applications of 540g/ha of Roundup at the 2-3 leaf stage with a cultivation in between. This is also the approach recommended to minimise the risk of resistance development.

“Where you’re only spraying once ahead of autumn drilling after more than six weeks or so you need to increase the rate to 720 g/ha to deal with better established, tillered weeds. This higher rate is also important where ryegrass or bromes are present.“

Attention to detail in spraying practice is every bit as important in making your pre-planting applications work as hard as they can; especially water volume, nozzle type, spray pressure, boom height and forward speeds,” adds Mr Bradbury.

“Where your drilling is delayed for more than a few days after pre-planting treatment, you should seriously consider including an approved glyphosate included in the pre-em mix. A lot of black-grass can emerge in a very short time under the right conditions and it won’t be touched by most residuals.”

Visit out new Critical Advantage hub to get the expert advice you need to tackle black-grass and improve soil health this autumn HERE.