Optimising nutrition for late-drilled cereals

16th October 2025

Challenging weather conditions have pushed many cereal drilling operations well beyond optimal windows. Yara’s food chain business manager Mark Tucker explains how farmers can best manage the needs of crops that will struggle from the outset.

“While late drilling presents significant challenges, understanding the nutritional hurdles ahead and adapting strategies accordingly can mean the difference between salvaging a reasonable harvest and watching yields collapse,” said Mark Tucker.

The fundamental problem with late-drilled cereals stems from the inevitable decline in soil temperatures. As October progresses into November, soil temperatures drop below the thresholds needed for efficient nutrient cycling, setting off a chain of developmental problems that limit crop performance.

Chemical reactions that drive nutrient availability slow dramatically as temperatures fall, particularly affecting phosphate release from soil reserves.

This timing coincides with the period when young cereal plants exhaust their seed reserves and begin depending on soil nutrients for continued growth. The result is a nutrient availability gap that can stunt early development and compromise the entire season’s potential.

Mr Tucker explained the multiple challenges that stem from late drilling.

“The single biggest challenge comes from the fact that as autumn progresses, soil temperatures are dropping and there’s nothing you can do about that. The consequence of that is nutrient availability in the soil decreases because it’s chemically driven.

“As the crop starts to grow and exhaust some of that available nutrient, the replenishment through natural soil processes becomes very slow.”

This nutritional stress manifests in reduced tillering, smaller root systems, and lower biomass accumulation during the critical first 60 days of crop development. Late-drilled crops typically enter winter with compromised root architecture, making them more vulnerable to both drought and waterlogging stress in the following spring.

Heavier soils present particular challenges, cooling faster once saturated and becoming difficult to access for remedial applications. That means the window for foliar nutrition between drilling and Christmas becomes increasingly narrow, yet potentially crucial for maintaining crop momentum during establishment.

Strategic fertiliser management

Farmers must fundamentally shift their approach to fertiliser management for late-drilled situations. Traditional application timings and rates become inadequate when crops face shortened growing periods and disrupted nutrient availability.

Early nitrogen applications become critical, but the choice between liquid and solid forms requires careful consideration of seasonal conditions. Dry spring weather favours liquid applications for rapid uptake, while urea-based products can struggle in cold, dry conditions where conversion to plant-available forms slows significantly.

“Late drilled cereals should be the target crops for getting out very early with that first application of nitrogen,” Mr Tucker noted.

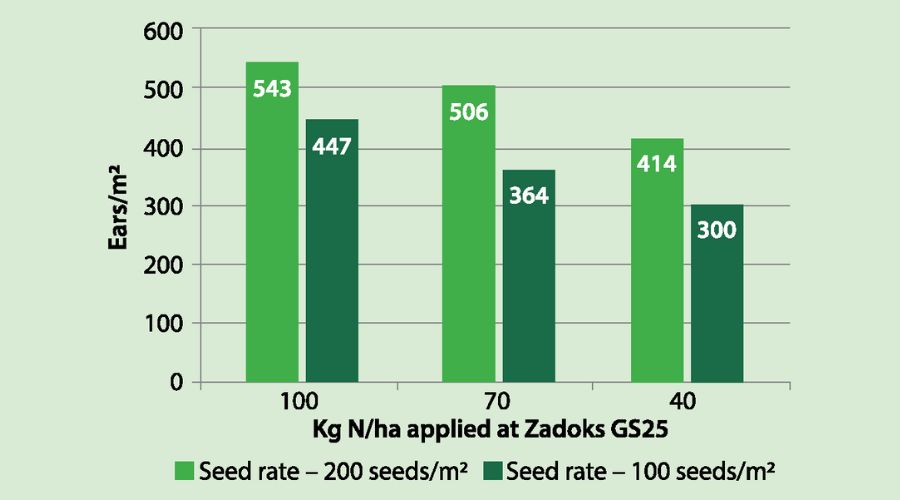

“Rather than a typical first application which might be 40–50kg of nitrogen per hectare, for those late drilled crops we should be thinking about 70–80kg of nitrogen per hectare as that first dressing to really get the crop going quickly.” (see Graph 1)

This front-loaded approach mirrors historical second wheat management, where higher early nitrogen rates compensate for reduced tillering capacity and shorter development windows.

The strategy requires biasing total nitrogen allocation toward early applications while maintaining flexibility for later adjustments based on crop response.

Phosphate management becomes equally critical, particularly on soils with historic deficiencies. Cold soil conditions that inhibit natural phosphate release can be partially offset by fresh fertiliser applications that remain available in soil solution longer than under warm conditions.

Early foliar phosphate applications, either in autumn if conditions permit or as T0 treatments in spring, can provide the boost needed for root development and early vigour.

Biological solutions and stress management

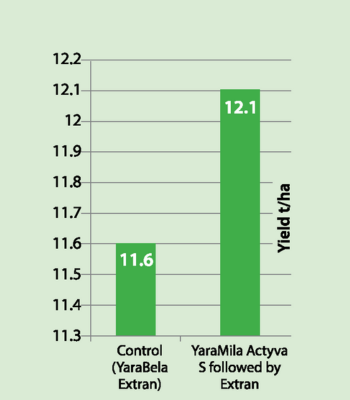

Late-drilled crops face inherently higher stress levels throughout their development, making them prime candidates for biological interventions. While the evidence base for biostimulants remains variable, the challenging conditions these crops encounter justify their inclusion in nutrition programmes.

The key is maintaining growth momentum when crops encounter stress. Plants naturally respond to stress by slowing or stopping growth to redirect resources toward survival mechanisms.

For late-drilled crops constrained by late establishment, any growth interruption can prove catastrophic. Biostimulants are compatible with both liquid and solid fertiliser programmes, and they provide potential insurance against stress-induced stalls in growth.

Current growing conditions may actually favour late-drilled establishments from a nutritional standpoint. Warm summer conditions and drought stress have likely created higher residual nitrogen pools due to reduced uptake by previous crops. This enhanced nitrogen availability, combined with improved soil structure from drought-induced cracking, could provide better starting conditions than usual for late sowings.

Economic targeting and monitoring

Economic pressures demand careful planning around input allocation for late-drilled crops. The greatest return on nitrogen investment comes from the first 100kg per hectare, delivering 5–6:1 returns compared to 2.5:1 or less for the second and third applications.

“The nitrogen investment is going to be probably the single most important one,” Mr Tucker emphasised. “The biggest return comes from that first 160kg of nitrogen, and particularly the first 80kg. So that is where you wouldn’t skimp.”

He suggested concentrating resources on early, high-impact applications while maintaining flexibility to adjust final dressings based on seasonal conditions and commodity prices.

Monitoring strategies must also be adapted to late drilling realities. Limited leaf material restricts tissue testing opportunities, making historic soil and grain analysis data more valuable for risk assessment and field prioritisation.

Farmers should develop risk-scoring systems for fields, considering drilling date, soil type, and historic nutrient status to guide resource allocation.

The AHDB wheat growth guide provides essential targets for shoot and ear numbers, allowing realistic assessment of whether crops can achieve profitable yields. Understanding these benchmarks enables informed decisions about continued investment versus cutting losses.

When it comes to crop-specific considerations, barley crops require particular attention due to their inflexible yield structure. Unlike wheat’s ability to compensate for low ear numbers through increased grain numbers per ear, barley offers no such elasticity. Getting plant populations and early nutrition right becomes critical for barley crops drilled late.

“Late drilling forces farmers into difficult decisions with very tight timeframes,” Mr Tucker concludes.

“Success means throwing out the rulebook and focusing everything on intensive early nutrition, smart economic choices, and being honest about what yields are realistic. The challenges are significant, but farmers who understand what they’re up against and adjust their approach accordingly can still make these crops pay their way.”

Read more arable news.